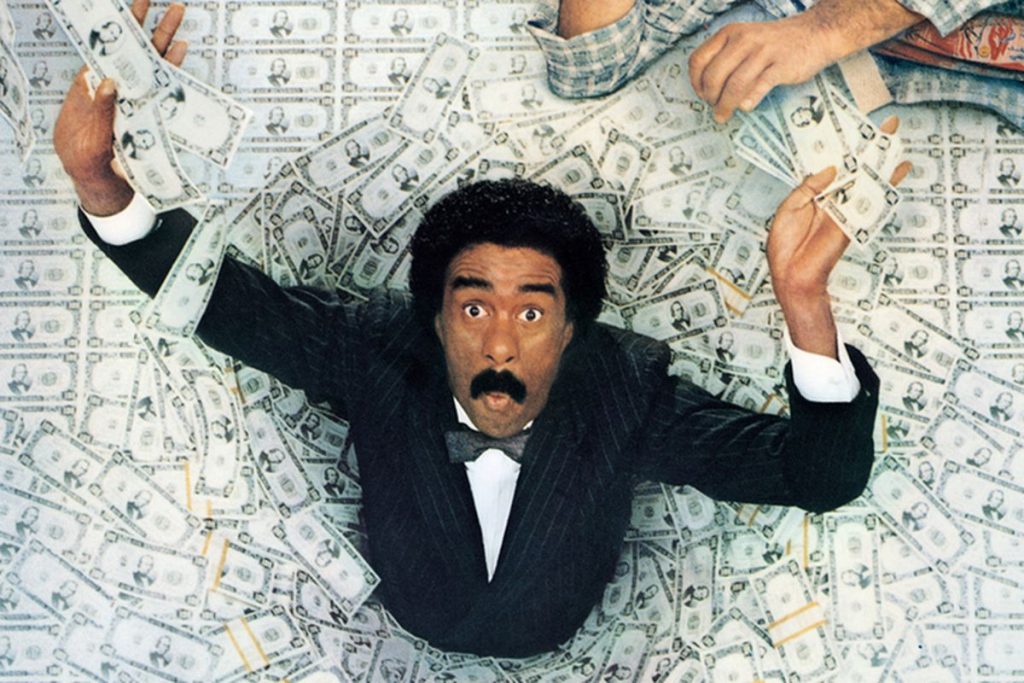

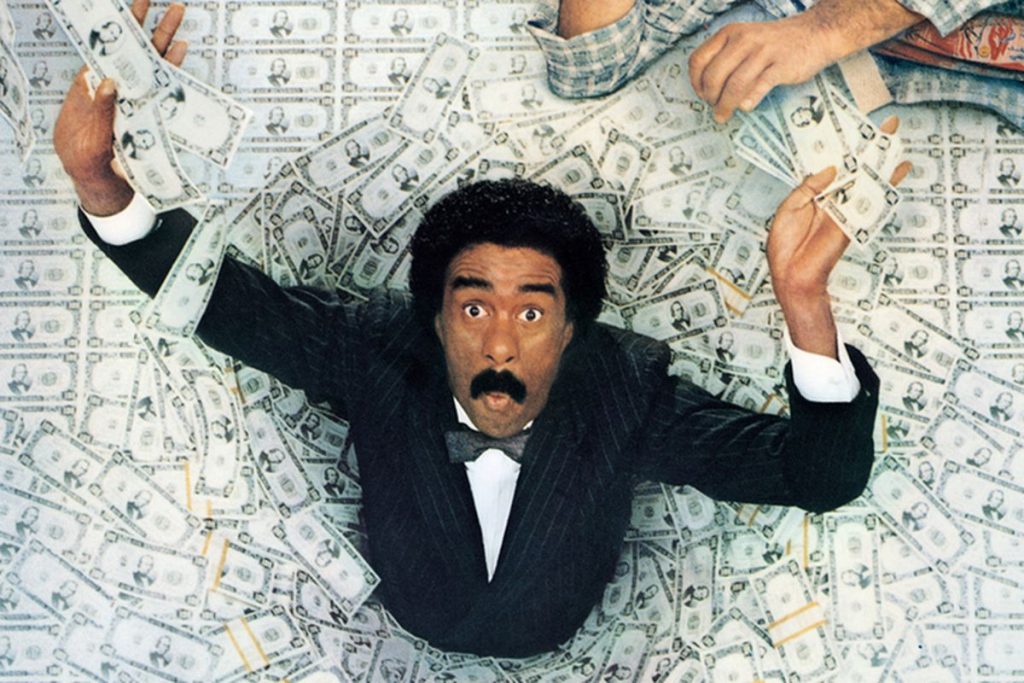

In the 1985 Hollywood film “Brewster’s Millions”, Richard Pryor stars as Monty Brewster.

Brewster’s great-uncle dies and leaves him his entire $300 million estate but only if he can complete a challenge with several conditions.

Under the Will, Brewster is offered two alternatives; take $1 million up front; or spend $30 million within 30 days to inherit the entire $300 million estate. There are several other conditions attached to the second alternative;

- Brewster may not own any assets that are not already his at the end of the 30 days;

- he must get value for the services of anyone he hires;

- he may donate 5% to charity and lose 5% by gambling;

- he may not waste the money by purchasing and destroying valuable objects; and

- he is not allowed to tell anyone!

As this is Hollywood, of course Brewster accepts the challenge!

Being a killjoy lawyer type, this film only caused me to wonder “would such a conditional Will be enforceable?” Perhaps Brewster should simply have brought a Court challenge to the conditions in the Will arguing that they were unenforceable. That certainly would have been an exciting plot twist for the film – 120 minutes of oral arguments on the validity of Will clauses! What a blockbuster!

In the case of Hickin v Carroll (2014) the New South Wales Supreme Court was called upon to determine the validity of a conditional gift in a Will. Mr Carroll, who died in 2012, left a Will which provided for conditional gifts to be made to his children on the following terms;

I make the following gifts of remainder to my children subject to and dependent upon them becoming baptised into the Catholic Church within a period of three months from the date of my death and such gifts are also subject to and dependent (sic) my children attending my funeral

The children attended the deceased’s funeral but did not “become baptised into the Catholic Church” within the three month period. The children were all Jehovah’s Witnesses (something the deceased, apparently, objected to).

The Court found that, in order to be valid, a conditional gift in a Will must be;

- Certain;

- Possible to perform; and

- Not contrary to public policy.

Certainty

The Court found the conditions were certain in that they were clearly expressed and capable of being understood. The children could easily have demonstrated that they had satisfied the baptism condition if they chose to comply with it.

Not Impossible

The Court took the view that the baptism condition was not impossible to perform even though there may have been practical difficulties in finding a Catholic priest willing to perform the relevant ceremonies within the 3 month time limit.

Public Policy

The Court also found that conditions in a Will that are “in restraint of religion” are not against public policy and, as such, are valid. His Honour stated;

The conditions, in particular the Baptism Condition, do not impinge upon whatever right to the free exercise of their religion the law now accords the Children. The Gifts do not compel the Children to do anything. If they had chosen to do so, they could have complied with the Baptism Condition. They have maintained their adherence to the Jehovah’s Witness faith. That choice is to be accorded every respect but does not relieve them from the consequences of that choice on their eligibility under the Gifts.

Conclusion

In the end, the Court found that the conditions in Mr Carroll’s Will were certain, possible to perform and not against public policy. They were valid conditions and, by failing to comply with them, the children missed out on their inheritance.

Brewster’s Case

Would a Will similar to that in Brewster’s Millions be valid in NSW?

Let’s look past the fact that, for dramatic purposes, the Will in the film is embodied in a video. Let’s assume it was in written form. The conditions are sufficiently clear. Accordingly, such a Will would likely pass the first two tests of; certainty and impossibility.

A spirited debate would likely be had over whether the conditions were void as contrary to public policy.

The Courts do object to the waste or destruction of estate assets and property. Given that the Brewster Will actively called for the beneficiary to “burn through” $30 million in 30 days, (including by gambling and giving away the funds), is that not a waste or destruction of estate assets?

However, on the other hand, the Courts are also reluctant to place restrictions on testamentary freedom. Unless a condition actively promotes the commission of a crime, it is hard to see the Court making a value judgement about the morality of a condition requiring such profligate spending.

On balance, the Brewster Will, if in writing would be valid in New South Wales.

Contact me for the rights to the re-make: Brewster’s Millions: 2 hours of oral argument before the Supreme Court.